Explore + Learn

The Black Boxes: Key to Understanding the Final Moments of Flight 93

Large commercial aircraft and some smaller commercial, corporate, and private aircraft are required by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to be equipped with two "black boxes" that record information about a flight. In the event of an aircraft incident or accident, investigators use the data from the black boxes to reconstruct the events leading to the event. One of the black boxes, the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), records radio transmissions and sounds in the cockpit while the other, the Flight Data Recorder (FDR), monitors parameters such as altitude, airspeed, and heading.

Both recorders are typically installed in the tail of the plane, the most crash-survivable part of the aircraft. The boxes themselves are made of stainless steel or titanium and made to withstand high impact velocity or a crash impact of 3,400 Gs and temperatures up to 2000 degrees F (1,100 degrees C) for at least 30 minutes. The recorders inside are wrapped in a thin layer of aluminum and a layer of high-temperature insulation. Though popularly known as “black boxes,” the steel cases that protect the sensitive recording devices inside are painted high-visibility orange so they can be more easily spotted at a crash site. Underwater locator beacons assist in recovering recorders immersed in water.

The CVR records the flight crew's voices, as well as other sounds inside the cockpit using microphones usually located in the overhead instrument panel between the two pilots and in the headsets of the pilots. Sounds of interest to an investigator include engine noise, stall warnings, landing gear extension and retraction, and other recognizable clicks and pops. Communications with Air Traffic Control and conversations between the pilots and cabin crew are also recorded by the CVR.

The FDR onboard the aircraft records many different operating conditions of the flight such as altitude, airspeed, heading, fuel usage, autopilot status, and aircraft attitude. With the data retrieved from the FDR, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) can generate an animated video reconstruction of the flight that enables the investigating team to combine the data from the CVR and FDR to visualize the last moments of the flight before the accident.

The NTSB is an independent Federal agency charged by Congress with investigating every civil aviation accident in the United States and significant accidents in other modes of transportation – railroad, highway, marine, and pipeline. The NTSB determines the probable cause of the accidents and issues safety recommendations aimed at preventing future accidents. Following an aviation accident, NTSB investigators are immediately dispatched to the scene to begin gathering evidence and undertake the search for the black boxes. When the boxes are found, they are immediately transported to NTSB headquarters in Washington, DC for processing. Using sophisticated equipment, the information stored on the recorders is extracted and translated into an understandable format. While complete reports on NTSB investigations can take years, the NTSB laboratories work quickly to analyze black box data so that the findings can help guide the on-going field investigation. According to a September 14, 2014 Washington Post article, “Unraveling the mystery when a plane falls from the sky,” listening to the final words from the cockpit is considered “a sacred duty” at the NTSB laboratory. “They slip on headphones, sit before individual computer screens and begin to listen, not just to voices, but to every noise that was recorded.” Later, the NTSB issues a transcript as part of its final report, but does not release the audio.

United Airlines Flight 93 was equipped with a solid-state CVR measuring 12.5” long x 5” wide x 6” high, weighing about 11.5 pounds. This model was capable of retaining the most recent 30 minutes of audio from the cockpit, meaning that older information was over-written by new data collected beyond the 30-minute recording limit. The CVR records 4 distinct channels. One channel contains audio information from an open cockpit area microphone (CAM) that is mounted in the center of the cockpit above the windshield. The remaining 3 channels contain aircraft radio information from microphones in the Captain’s, First Officer’s, and cockpit jump seat’s headsets.

Cockpit Voice Recorder

The FDR on Flight 93 was a solid-state, digital model measuring 19.5” long x 5” wide, x 6” high. It was capable of recording data from the entire flight from take-off to crash.

Flight Data Recorder

Both black boxes on Flight 93 were located in the tail section of the aircraft.

When investigators arrived at the crash site in Stonycreek Township, Somerset County, on September 11, 2001, the search for the black boxes was their top priority. Investigators from the NTSB arrived on the afternoon of September 11 to begin their work.

At a press briefing on September 12, 2001, FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Roland Corvington holds up a photo of the black boxes they hope to recover at the Flight 93 crash site. “The search will be painstaking,” Corvington said. “The value of the black box and the information therein cannot be overstated. Until we recover that, we won’t be able to answer any of the questions you’re asking.” (“Painstaking search begins in Shanksville,” Mike Faher, Johnstown Tribune-Democrat, September 13, 2001)

At a press briefing on September 12, 2001, FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Roland Corvington holds up a photo of the black boxes they hope to recover at the Flight 93 crash site. “The search will be painstaking,” Corvington said. “The value of the black box and the information therein cannot be overstated. Until we recover that, we won’t be able to answer any of the questions you’re asking.” (“Painstaking search begins in Shanksville,” Mike Faher, Johnstown Tribune-Democrat, September 13, 2001)Photo by Dale Sparks

The FBI reasoned that, due to the collateral damage of the buildings at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Flight 93 crash site would be the most likely place to recover critical evidence, including the black boxes. Beginning September 12, teams of investigators began to simultaneously excavate the crater, and systematically search the surrounding woods and fields. Local contractors were hired to use heavy equipment to begin the excavation while investigators from the FBI, the FAA and the NTSB observed closely, hoping that the black boxes would be uncovered. It was a tense period, as all of the workers were focused on the importance of quickly recovering this key evidence, while working methodically and carefully so the boxes would not be further damaged during excavation.

During the excavation of the Flight 93 crash site watchers were stationed around the pit, hoping to spot the bright orange color of the boxes.

During the excavation of the Flight 93 crash site watchers were stationed around the pit, hoping to spot the bright orange color of the boxes.Photo by Pennsylvania State Police, Chris Pushart

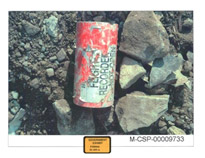

On Thursday, September 13 at 4:20 pm, workers uncovered the FDR from the crater at a depth of 15 feet. The cylinder-shaped box was photographed as it was uncovered in the crater. FBI agents assumed custody of the box, logged it as evidence, and immediately removed it from the site, flying it to the NTSB laboratory in Washington, DC where its contents could be analyzed.

The FDR as first seen in the crater excavation on September 13.

The FDR as first seen in the crater excavation on September 13.Photo by Ron Horak

Because the memory board showed signs of impact damage, the FDR was taken from Washington, DC to Honeywell facilities in Redmond, Washington for evaluation and downloading. The data were extracted and electronically transferred to the NTSB.

Meanwhile at the crash site, the search continued for the second black box. On Friday, September 14 at 8:30 pm, the CVR was recovered from the crater at a depth of 25 feet. Again, the FBI assumed custody of the box, and flew it to NTSB headquarters in Washington, DC.

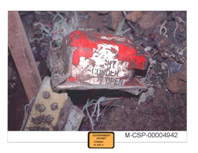

Flight Data Recorder as recovered at the Flight 93 crash site on September 13, 2001.

Flight Data Recorder as recovered at the Flight 93 crash site on September 13, 2001. Cockpit Voice Recorder as recovered at the Flight 93 crash site on September 14, 2001.

Cockpit Voice Recorder as recovered at the Flight 93 crash site on September 14, 2001.In the weeks following September 11, 2001, the fact that both flight recorders from Flight 93 were recovered and yielded evidence took on increased importance. At the World Trade Center site, none of the four recorders on the two hijacked aircraft were recovered in the building rubble. At the Pentagon site, both boxes from Flight 77 were recovered, but the CVR was so badly damaged that it did not yield usable information.

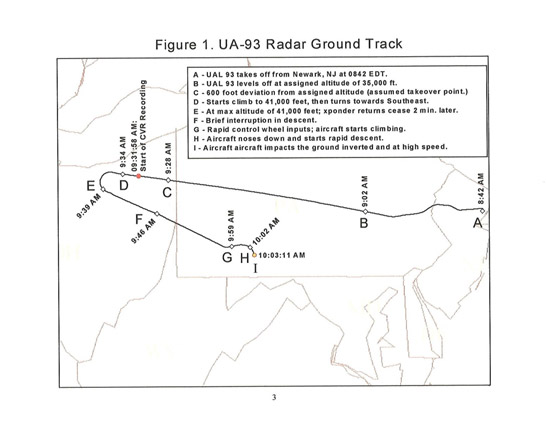

In February 2012, the NTSB released four reports utilizing data from the Flight 93 FDR: the “Factual Report of Investigation” of the FDR consisting of graphs and tables summarizing the output of the FDR during the entire flight, the “Recorded Radar Study,” the “Study of Autopilot, Navigation Equipment, and Fuel Consumption Activity,” and the “Flight Path Study.” The “Study of Autopilot” report includes graphs illustrating the values of speed, altitudes, headings, and climb/descent rates over the duration of the flight and describes changes in the magnetic heading entered in the Mode Control Panel that indicate that Flight 93 was on a heading for Washington, DC. The report also indicates that the VOR (very high frequency omnirange station) receiver on Flight 93 was set to correspond with the VOR station at Washington Reagan National Airport (DCA), suggesting “that the operators of the airplane had an interest in DCA and may have wanted to use that VOR station to help navigate the airplane towards Washington.” Data retrieved from the FDR allowed the NTSB to calculate that Flight 93 had about 37,500 pounds of fuel remaining when it crashed in Pennsylvania. The “Flight Path Study” shows the flight path of the aircraft and its altitude for the 1 hour and 21-minute duration of the flight and includes a transcript of aircraft-to-ground communications. The report concludes with this summary of the flight’s final moments of erratic flight:

At 9:59 the airplane was at 5,000 feet when about 2 minutes of rapid, full left and right control wheel inputs resulted in multiple 30 degree rolls to the left and right. From approximately 10:00 to 10:02 there were four distinct control column inputs that caused the airplane to pitch nose-up (climb) and nose-down (dive) aggressively. During this time the airplane climbed to about 10,000 feet while turning to the right. The airplane then pitched nose-down and rolled to the right in response to flight control inputs, and impacted the ground at about 490 knots (563 mph) in a 40 degree nose-down, inverted attitude. The time of impact was 10:03:11.

Normally, the audio of a CVR recovered from a crash scene is heard only by the team of investigators and representatives of the airline and the aircraft manufacturer and others who can assist in accurately interpreting the recording. In the case of Flight 93, family members of the passengers and crew began lobbying for permission to hear the recording within months of their loved ones’ death. Eventually, permission was granted, and in April, 2002, the FBI invited representatives of each family to a secure, private location to listen to the audio while viewing the transcript. They were asked not to speak with the media or others about what they heard pending use of the recording in criminal proceedings against terrorists associated with the hijacking.

The transcript of the Flight 93 CVR was issued publically during the April 2006 sentencing trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, an al Qaeda associate who “unlawfully, willfully and knowingly combined, conspired, confederated and agreed to kill and maim persons within the United States . . . resulting in the deaths of thousands of persons on September 11, 2001.” The jury was permitted to listen to the audio of the Flight 93 CVR and then, at the request of the Flight 93 family members, the judge in the trial ordered that the audio be “sealed” and only a transcript released.

Major newspapers across the country published the transcript on April 12, 2006. Later, the FBI released a more comprehensive version of the transcript which included details about which microphone source picked up the transmission, descriptive words and phrases such as “sound of seat belt” and “sound of loud click” and “the start of series of very loud crashes,” and details about the gender and language of the speaker, such as “a very loud shout, by a native English speaking male.”

The words in bold in the transcript are translated Arabic text and those in Italic font are English text. (The hijackers are known to have spoken in both English and Arabic.) Words in upper case are shouted. The transcript also includes transmissions recorded from Cleveland Air Traffic Control Center as Air Traffic Controllers attempted to contact the flight crew. This more-detailed transcript is reproduced here.

The recording from Flight 93’s CVR begins at 9:31:57 am and continues until the time of the crash at 10:03:11. Unfortunately, the moment when the flight was overtaken by terrorists, 9:28, and the first few minutes of the hijacking event are not part of the audio retained by the CVR because the CVR retains only the most recent 30-31 minutes of audio. [Note: Air Traffic Control recordings from 9:28:19 and 9:28:54 help fill in this audio gap. The “Mayday” call from Captain Dahl and First Officer Homer, along with the sounds of a struggle, is heard by personnel at the Cleveland Air Route Traffic Control Center and by pilots of other aircraft using the same radio frequency. See “Summary of Air Traffic Hijack Events, September 11, 2001,” Federal Aviation Administration.]

Tony James, the FAA investigator in charge, summarized what it meant to recover the black boxes from Flight 93: “From the time I got there, I knew how important this was going to be for them to find those boxes . . . The voice recorder and the flight data recorder [were] the most critical of all the evidence because the, the cockpit voice recorder . . . basically told the story of what happened inside the airplane. The flight data recorder told what happened to the airplane itself.”

For those who are able to decipher and translate the muffled, chaotic, and overlapping sounds and voices recorded by the CVR and decode the thousands of pieces of data captured by the FDR, the black boxes are indeed critical pieces of evidence. There will always be unanswered and unanswerable questions about what happened during the final moments on board Flight 93. It is because the recorders functioned properly and because investigators were able to find and safely recover them that we do know something about the unimaginable situation faced by the passengers and crew on Flight 93 and their courageous response.